Séamus Connolly: A Living Legend in Irish Traditional Music

by Dr. Earle Hitchner

During 2013 and 2014, fiddler, teacher, author, composer, recording artist, album producer, summer school and festival founder, and concert and lecture series organizer Séamus Connolly received three prestigious awards. The first was the Ellis Island Medal of Honor, bestowed in 2013 by the National Ethnic Coalition of Organizations in recognition of distinguished career achievement by an immigrant or descendant of immigrants to the United States. The second was the National Heritage Fellowship, bestowed in 2013 by the National Endowment for the Arts in recognition of distinguished lifetime achievement by a folk or traditional artist residing in the United States. The third was local: the Faculty Award, bestowed in 2014 by the Boston College Arts Council to honor outstanding achievements in and contributions to the arts by a faculty member of Boston College, from which Séamus retired on December 31, 2015, capping a quarter century of extraordinary service.

All three awards underscore the crucial, enduring importance of Séamus Connolly’s accomplishments in preserving, promoting, and passing on his love for and consummate skill in Irish traditional music. No single award reflects those accomplishments more than the NEA’s National Heritage Fellowship, deemed the pinnacle honor for a folk or traditional artist living in the United States. That National Heritage Fellowship in 2013 ushered Séamus, a longtime Massachusetts resident now living in Maine, into an elite company of previous Irish and Irish-American recipients: sean-nós (old-style) singer Joe Heaney in 1982, uilleann piper Joe Shannon in 1983, fiddler and teacher Martin Mulvihill in 1984, stepdancer and choreographer Michael Flatley in 1988, flutist Jack Coen in 1991, fiddler Liz Carroll in 1994, stepdancer and choreographer Donny Golden in 1995, singer and multi-instrumentalist Mick Moloney in 1999, fiddler Kevin Burke in 2002, button accordionist Joe Derrane in 2004, and flute, whistle, and uilleann pipes player Mike Rafferty in 2010. Joining those twelve as National Heritage Fellowship recipients were two more Irish Americans: stepdancer Kevin Doyle in 2014 and button accordionist Billy McComiskey in 2016.

I have been writing about Irish traditional music and musicians since 1978, and in my roles as critic and columnist, I cannot think of anyone who is more qualified and deserving of this extremely rare combination of honors than Séamus Connolly, whose reputation in Ireland is no less lustrous. There is no hint of hype or whiff of wishful thinking in stating that Séamus Connolly is one of the living legends of Irish traditional fiddling in the world.

I had first heard about Séamus from a number of U.S. resident musicians who had lived in Ireland during the early 1960s and were quite aware of his celebrated friendly rivalry back then with Armagh fiddler Brendan McGlinchey at Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann, Ireland’s most hallowed traditional music festival and most rigorous competition. Those two were widely acknowledged as the young fiddle titans of their generation, and the virtuosity of one seemed to spur the virtuosity of the other, creating an intense, mutually respectful duel of horsehair bows that is still recalled with fond admiration by those who watched and heard it firsthand. Out of that nearly folkloric early rivalry between the two has sprung a friendship lasting to this day. It is a testament to what competitiveness can foster when it starts in mutual inspiration and appreciation.

Séamus Connolly has the distinction of being one of just five fiddlers (as of 2016) ever to win two All-Ireland senior solo championships and the only fiddler ever to win both the under-age-18 solo title and the senior solo title in the same year, 1961, before the rules were changed. Even more impressive is the fact that no one in the history of Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann, founded in 1951, has won more overall All-Ireland solo fiddle championships than Séamus: ten. Besides that unmatched total, he won the coveted Fiddler of Dooney title in 1967 in Sligo, where Ballybofey, Donegal-born fiddling master Hughie Gillespie (1906-1986) was one of the adjudicators and where Séamus met for the first and last time another fiddling master, Killavil, Sligo-born, and longtime New Yorker James “Lad” O’Beirne (1911-1980), who was in the audience. Séamus also won four separate duet titles (two on fiddle and flute, and two on fiddle and uilleann pipes) with Kilmaley, Clare, instrumentalist Peadar O’Loughlin at the Oireachtas championship competition in Dublin.

Commanding encomium equal to that for his music are Séamus Connolly’s integrity and generosity. When I was hosting and programming a noncommercial radio show devoted exclusively to Irish and other Celtic traditional music from 1984 to 1989 in the greater New York/New Jersey metropolitan area, I organized an initial fund-raising concert in support of my program and the radio station at an American Legion hall in Lyndhurst, New Jersey. I asked Séamus, who then lived in Massachusetts, if he would perform at the concert. He said yes, but I remember thinking at the time that he was just being nice or polite. I did not contact him further. Yet on the night of the concert, he was the first musician to arrive. He had driven all the way down from his Massachusetts home, and, after performing and otherwise making himself available all night long, he drove back. Séamus Connolly is a man of his word—in this case, “yes,” his one-word reply to my lone request. He has repeated that gesture at other times in other situations, and each instance reminded me of his selflessness as well as his commitment to and passion for Irish traditional music.

Séamus Connolly with his mother, Lena Connolly, in Killaloe, circa 1987. Photo by Michael Connolly.

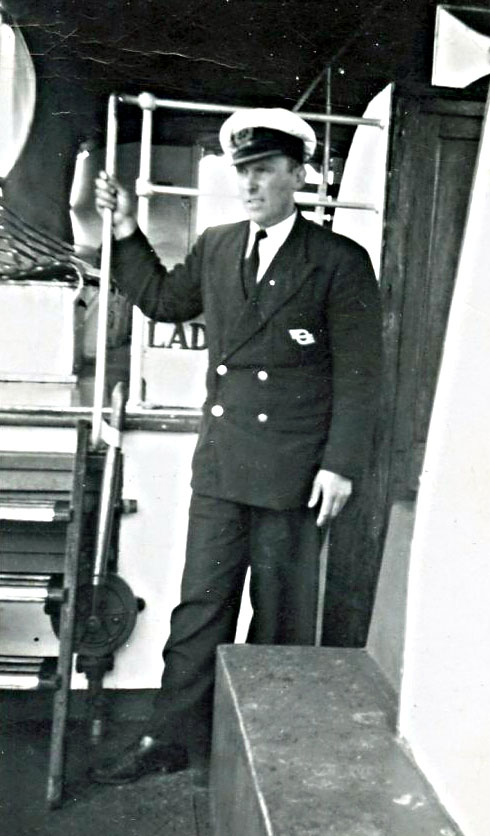

Michael "Mick" Connolly, captain of the passenger cruiser St. Brendan, circa 1955. (Box 17 Folder 4, Séamus Connolly Papers, John J. Burns Library, Boston College)

Born on April 2, 1944, in Killaloe, County Clare, Ireland, Séamus Connolly is the son of Lena Connolly (née Collins), a homemaker, who played piano, button accordion, and, to some extent, fiddle, and Michael "Mick” Connolly, the skipper of the pleasure cruiser St. Brendan and later a tugboat on the River Shannon, who played flute, whistle, and button accordion and was also a stepdancer of singular style. Séamus’s older brother, Michael, currently the choirmaster and organist at St. Flannan’s Church in Killaloe, plays piano, and their younger brother, Martin, plays button accordion and also makes the instrument by hand under his Kincora imprint in Ennis, County Clare. Though not a musician, homemaker and oldest sibling Marie enjoys Irish traditional music with equal fervor. Together, the Connollys turned their household into a nurturing hub of music.

A true wunderkind on fiddle, Séamus grew in demand as a soloist. He was invited to contribute two tracks, accompanied by Galway’s Micheál Ó hEidhin on piano, to The Rambles of Kitty, a 1967 Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann LP reissued as a CD in 2007. Moreover, Séamus’s various musical alliances in Ireland—the Kilfenora and Leitrim céilí bands (the latter won the 1962 All-Ireland senior céilí band title with Séamus as a member), Inis Cealtra (comprising Séamus Connolly and Paddy Canny on fiddles, Tipperary’s Paddy O’Brien on button accordion, Peadar O’Loughlin on flute, and George Byrt on piano), and especially Séamus’s legendary partnership with Paddy O’Brien—constitute, in and of themselves, outstanding achievements. And The Banks of the Shannon, the 1974 “little LP” of six tracks (reissued as a CD with nine other tracks in 1993) made by Séamus with O’Brien and pianist Charlie Lennon, is an indisputable masterpiece.

Séamus Connolly’s feats on the fiddle were the stuff of legend across Ireland by 1976, the year he immigrated to the United States and four years after he had initially visited as a member of the first Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann North American tour. It is hard to imagine equaling, let alone outshining, his exceptional musical legacy in Ireland, but Séamus did precisely that in the United States.

Whether through private tutelage, classroom instruction, summer school curricula, or music camp workshops, he has steadfastly taught U.S.-born students the techniques and regional styles of Irish traditional fiddling. Among his more prominent pupils were Boston-born Gráinne Murphy, a past member of the internationally popular band Cherish the Ladies; Rhode Island-born Sheila Falls, who is assistant professor of music in performance and director of the World Music Ensemble at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts; and Boston-born Brendan Bulger, who won the All-Ireland under-age-18 fiddle championship in 1990 and was inducted into Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann’s Northeast Region (of North America) Hall of Fame in 2011. All three of those former students have recorded fine solo albums attesting to the positive impact of their teacher: Bulger’s The Southern Shore, produced by Séamus in 1991, and the self-titled Brendan Bulger in 2001, Falls’s All in the Timing in 2009, and Murphy’s Short Stories in 2010.

In the estimation of Bulger, Séamus Connolly’s impact on Boston’s Irish traditional music scene is especially salient. “His teaching and stylistic influence will be felt for generations to come in Boston,” Bulger told the Boston Irish Reporter newspaper in 2010. “It is a testament to his great personal and musical presence that in an age when local, geographically delineated styles are eroded by ease of migration and the ability to share music electronically, he has left a clearly discernible and lasting impression on the community of Boston fiddle players who have known him. It is a rare accomplishment and an important one that a large, fundamental section of the definition of Boston-based Irish fiddle playing style during the late 20th century to early 21st century can be directly attributed to his influence. He has steadily and unassumingly created an enormous, even worldwide profile for Boston Irish fiddle playing in conjunction with many others, and should be recognized as a primary driver in that process over the course of the past 30-plus years. Those effects will not erode quickly.”

From 1993 to 2003, Séamus Connolly was the director of the Gaelic Roots Summer School and Festival that he founded on the campus of Boston College in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. In the estimation of many, including myself, it was the finest Irish traditional music and dance summer school ever to emerge on U.S. soil. From the outset, Séamus was determined to use his very strong connections to bring Ireland’s best traditional musicians and dancers to Gaelic Roots so that they and their U.S. counterparts could gather together in one place at one time to share tunes, swap stories, and forge a more powerful musical bond between them. I emceed the inaugural festival in 1993 and a few others thereafter, and I also audited a few summer school workshops and attended several special events on the schedule, so I witnessed firsthand the deep, indelible effect on the singers, instrumentalists, dancers, students, and audience members who were lucky enough to be there during that decade-long run of Gaelic Roots. Happily, its legacy lives on as a vibrant series of concerts and lectures founded by Séamus and, until his retirement at the end of 2015, organized by him throughout each academic year at Boston College under the Gaelic Roots rubric. In March 2010, Boston’s Celtic Music Fest, better known as BCMFest, formally honored Gaelic Roots founder-director Séamus Connolly with a special tribute concert at Club Passim in Harvard Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Signature photograph for Boston College Gaelic Roots Festival by Gary Wayne Gilbert.

Séamus has performed at many major folk and traditional music festivals in the United States, including the National Folk Festival, Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife, Washington, D.C.’s Irish Folk Festival, and American Roots Fourth of July Celebration at the Washington Monument. He represented the best in Irish traditional music on the first “Masters of the Folk Violin” tour—he ultimately did three such tours—organized by the National Council for the Traditional Arts, the oldest U.S. folk arts organization, based in Silver Spring, Maryland. He also performed on the Folk Masters radio series broadcast nationwide on National Public Radio. And his international itineraries as a performer, teacher, and lecturer have taken him to Spain, France, Australia, England, and Canada in addition to Ireland.

In 1990, Séamus was one of three recipients—out of a pool of over 2,500 applicants—to win a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship Award. A year later, he was the subject of an excellent documentary film, The Music Makers: Séamus Connolly and Friends. The National Endowment for the Arts and Refugee Arts (Country Roads) recognized Séamus Connolly’s exceptional efficacy as an Irish traditional music instructor by awarding him three consecutive Master/Apprentice Grants. And in 2002, he was inducted into Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann’s Northeast Region (of North America) Hall of Fame and was named “Irish Traditional Artist of the Year” by the Irish Echo newspaper.

Among Séamus Connolly’s lengthy list of TV and radio appearances or profiles are NBC-TV’s Today Show in New York City, WCVB-TV5’s Chronicle in Boston, Kathleen Biggins’s A Thousand Welcomes on National Public Radio affiliate WFUV-FM in New York City, and A Celtic Sojourn, hosted by Clonakilty, Cork-born Brian O’Donovan on Boston’s National Public Radio flagship station WGBH-FM. Séamus initiated, produced, and co-hosted a weekly radio program of Irish traditional music sponsored by Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann on Boston’s WNTN-AM. He also co-hosted the Irish segments of the WGBH-FM/National Public Radio series Ethnicity.

Séamus has made or appeared on more than two dozen U.S. recordings, including a pair of highly lauded solo albums: 1988’s Notes from My Mind (remastered and reissued by him in 2006) and 1989’s Here and There, the latter selected as one of the top five Celtic/British Isles recordings for that year by the National Association for Independent Record Distributors and Manufacturers. Those two recordings offer compelling proof not only of Séamus’s skill as a fiddler but also of his skill as a composer. They feature his tunes “The Bridge at Newtown,” “The Thirteen Arches,” “Thoughts of Carignan,” “Bells of Congress,” and, in memory of his mother, “I’ll Always Remember You.” Besides the 1993 CD reissue of The Banks of the Shannon, which included an unaccompanied fiddle track by Séamus and three tracks by him with pianist Charlie Lennon, Séamus recorded Warming Up, a brilliant 1993 album with Jack Coen on flute, Martin Mulhaire on button accordion, and Felix Dolan on piano. In 2004, Séamus recorded another outstanding album, the aptly entitled The Boston Edge, with Joe Derrane on button accordion and John McGann on guitar and mandolin.

In 2002, Séamus Connolly and Laurel Martin, another of his fiddle pupils who would record and teach in her own right, co-authored the book Forget Me Not: A Collection of 50 Memorable Traditional Irish Tunes, published by Mel Bay Publications. In addition, Séamus and Laurel recorded those 50 tunes in ornamented and unornamented versions on two companion compact discs, which enable neophytes and journeymen to acquire those melodies in simple or embellished forms. Other musicians playing on some of the CD tracks include Joe Derrane, John McGann, and flutist Jimmy Noonan, who has been teaching Irish traditional music at Boston College since 1996.

But surely Séamus Connolly’s magnum opus is what you are now perusing: The Séamus Connolly Collection of Irish Music, produced and published in digital form by the Boston College Libraries. It is an extraordinary project with a large bounty of music available for free and readily accessible online to Irish music lovers and appreciators around the world. This collection features more than 330 tunes and songs in 10 playlists, offering mostly traditional and some original content, compiled by Séamus and performed by himself and an array of other standout musicians numbering well over 100.

One of the original tunes is “Miss Chrysandra Walter,” a beautiful slow air composed and named by Séamus for his wife that is played movingly by Boston Symphony Orchestra violinist Bonnie Bewick Brown with accompanying cello and viola. Also included is a selection of songs sung by such accomplished vocalists as Len Graham, Rita Gallagher, Ann Mulqueen, Pádraigín Caesar, Josephine McNamara, Robbie McMahon, and, from Prince Edward Island, Ed and Ruth Fitzgerald. Only the hornpipe “The Old Blackbird” is common to both the trade paperback Forget Me Not, where it’s played by Séamus Connolly and Laurel Martin on the companion compact discs, and The Séamus Connolly Collection of Irish Music, where it’s played by Castletownbere, Cork-born button accordionist Finbarr Dwyer (1946-2014). Dedicated to Chrysandra “Sandy” Walter (1947-2011) and Irish radio broadcaster and music collector Ciarán Mac Mathúna (1925-2009), The Séamus Connolly Collection of Irish Music is indisputably one of the most ambitious and momentous ventures ever undertaken in the United States by an Irish traditional musician.

Part of this collection’s genesis came from a remark made by renowned Sliabh Luachra fiddler Julia Clifford (1914-1997) from Lisheen, County Kerry, who generously played a large assortment of tunes for 16-year-old Séamus and asked him after certain ones, “You don’t have it, do you?” As he explained, “She wanted to be sure that she was adding new tunes to my repertoire and not repeating what I already knew.” That is what Séamus and the other musicians who contributed to this collection have also done: liberally sharing their talent and knowledge so that others might learn and grow in the music as they did through concentrated exposure to tunes and songs familiar, unfamiliar, or forgotten. This altruistic act of “paying it forward” helps to ensure the future health of a musical tradition cherished by every performer here.

To gauge further just how ardently Séamus Connolly is dedicated to the preservation and promulgation of Irish traditional music, you can visit the Irish Music Archives of Boston College’s John J. Burns Library, where the “Séamus Connolly Papers” are kept in no fewer than 97 boxes. They include 400 cassettes and several reel-to-reel tapes, now digitized, of priceless field recordings conducted by him with many of the great past masters of the tradition, as well as research notes and materials, correspondence, photographs, press clippings, awards, and publications. The items donated by Séamus to the Irish Music Archives date from 1929 to 2013 and thereafter. In spring 2013 the John J. Burns Library mounted an exhibit culled from those materials, “The Musical Roots of Séamus Connolly, Sullivan Artist in Residence in Irish Music,” the latter reflecting an endowed position established by the generosity of G. Craig Sullivan (Boston College Class of 1964) and his wife, Maureen, that Séamus held from its inception in 2004 to his retirement in 2015 at Boston College. His sporadic additions of new or newly found materials merely reaffirm that the “Séamus Connolly Papers” represent a unique, widening window into his far-reaching musical career and life.

As Sullivan Artist in Residence in Irish Music and as Gaelic Roots Music, Song, Dance, Workshop, and Lecture series organizer and director, Séamus Connolly had a crowded schedule without factoring in his performing, music researching and collecting, and other teaching. Not to be overlooked throughout all of that are still more examples of his giving impulse. Three memorable ones, which I witnessed firsthand, focused on his dear friend and frequent playing partner, Joe Derrane. The first was Séamus’s stellar performance at “A Concert for the Ages: An All-Star Tribute to Joe Derrane” on November 13, 2010, at the Fairfield Theater Company’s Stage One in Fairfield, Connecticut. The second was Séamus’s seamless organizing and superb fiddling at “The Genius and Growing Impact of Joe Derrane” event on September 22, 2011, in Boston College’s Gasson Hall. And the third was Séamus’s poignant playing of “I’ll Always Remember You” during the funeral Mass on July 29, 2016, inside Saint Mary’s Church in Randolph, Massachusetts, for Joe Derrane, who passed away seven days earlier at age 86.

Add in such historic recordings as 1991’s My Love Is in America, showcasing the March 25, 1990, Boston College Irish Fiddle Festival featuring Séamus and 15 other preeminent fiddlers, and 1997’s Gaelic Roots, a double CD he produced of performances recorded at the summer school and festival of the same name, and what you have is an arc of Irish traditional music attainment in both Ireland and the United States that is inarguably seismic.

Yet Séamus remains humble about the achievements he has compiled and the praise his achievements have elicited. He prefers to redirect the light of attention to older musicians whom he reveres. Decades ago at a festival sponsored by the Philadelphia Céilí Group at Fisher’s Pool in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, I remember Séamus telling me how eager he was to meet a musical hero of his: New York City native Andy McGann (1928-2004). In the same way I had acted in awe of first meeting Séamus, he had acted in awe of first meeting McGann, hailed in the United States and in Ireland as one of the most accomplished Irish traditional fiddlers ever. I have never encountered a musician of Séamus’s stature who is more deferential and openhearted toward master players preceding him. And like them, he has helped to chart a path in Irish traditional music so that others could follow.

Since his retirement from Boston College, Séamus has maintained an energetic schedule of performing and mentoring. Among those activities was serving as an invited special guest at the 2016 Catskills Irish Arts Week in East Durham, New York, and at the 2016 Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann in Ennis, County Clare. As part of Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann’s Fidil Beo concert series held in the theater complex of Glór, Séamus performed in a Connolly family concert alongside his brother Martin on button accordion, Martin’s son Damien on fiddle and button accordion, Damien’s wife Sally on flute, and their son Colman as well as Ennis friend Geraldine Cotter on piano. Three aspects of the concert made it even sweeter for Séamus: It was the first time that he, Martin, Damien, Sally, and Colman formally played together on stage; it drew the largest audience in the entire Fidil Beo series; and it was Séamus’s first direct participation at Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann in 26 years. The standing-room-only turnout and the standing ovation from the crowd confirmed that Séamus’s fame as a fiddler and the esteem for the Connolly family name in music remain ascendant in his native county and country.

The result of almost 15 years of careful conception, development, and attention to detail, The Séamus Connolly Collection of Irish Music will undoubtedly raise Séamus Connolly’s already lofty reputation as a quintessential presence in Irish traditional music. “I believe talent carries a responsibility to use it well,” he said. “My memories of musicians like Julia Clifford helping me along the way have motivated me to do something similar for others.”

This collection, huge in scope and likely impact, is another instance of his transcendent talent put to exceedingly good use. He has given us so much for so long, and he is nowhere near finished. For Séamus Connolly, music is central to life, and his has incalculably enriched our own.

Earle Hitchner, who earned a doctorate with distinction from Drew University in 2015, has been called “arguably the pre-eminent Celtic critic in this country” by The Boston Globe, “the foremost Irish music critic in the United States” by the Boston Irish Reporter, and “one of the most authoritative commentators on Irish music on the international scene” by Ireland’s Treoir magazine. Among the newspapers, magazines, journals, and books to feature his writing on music are The Wall Street Journal, Billboard, Irish Echo, Irish Voice, Irish America, Irish Music, An Gael, The Companion to Irish Traditional Music, The Grove Dictionary of American Music, Journal of the Society for American Music, MTV’s Sonicnet, The Oxford American, Rhythm Music, New Choices, and Boston College Magazine. He has also written liner notes for 70 recordings, including the Boston Pops Orchestra’s The Celtic Album that was nominated for a Grammy award in 1998, and appeared in four film documentaries about Irish traditional music that have been broadcast on PBS-TV.